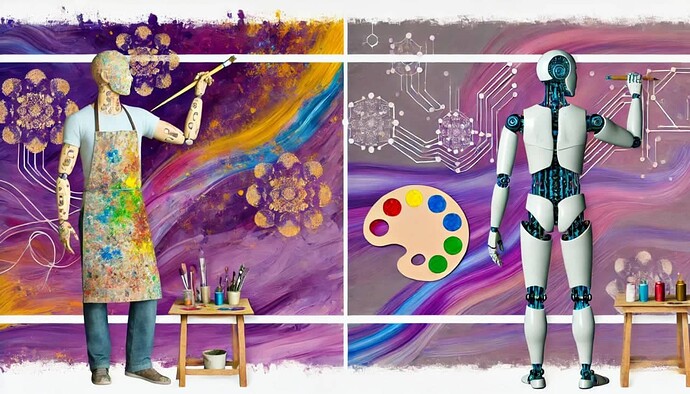

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) as a tool for art production has sparked a profound philosophical, ethical, and cultural debate. At the center of this conversation is a provocative question: Does the use of AI in art diminish the value of human creativity? This question does not only concern artists and technologists but also philosophers, ethicists, psychologists, and the general public. As AI systems become increasingly capable of producing paintings, music, poetry, and other forms of creative work, traditional notions of originality, authorship, intention, and expression are being challenged. Proponents of AI art argue that it democratizes creativity and expands artistic boundaries. At the same time, critics worry that reliance on machines could erode the authenticity and spiritual depth of human-made art.

This essay will explore the multifaceted nature of creativity, the historical context of art and technology, the operational mechanics of AI-generated art, and how human and machine contributions are evaluated. Through this examination, we will assess whether AI in art truly diminishes the value of human creativity or whether it offers new dimensions and paradigms for human expression.

1. Understanding Human Creativity

Creativity has long been regarded as one of human cognition’s most enigmatic and revered aspects. It is not merely producing something new; it involves originality, emotional resonance, cultural relevance, and intentionality. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the psychologist best known for his work on “flow,” defines creativity as a process that results in a novel and appropriate product, produced through interaction with a specific domain and culture. This framework places human creativity within a social and historical context: creative work is meaningful because it resonates with others, evokes emotions, or shifts perspectives.

Human creativity is also profoundly personal. It is often inspired by lived experience, sociopolitical realities, spiritual or existential contemplation, or the emotional turbulence of love, loss, and longing. Great artists like Van Gogh, Frida Kahlo, and Beethoven poured their inner struggles into their art. Creativity thus becomes a bridge between the personal and the universal—a vessel for empathy, connection, and shared humanity.

Furthermore, creativity involves effort, failure, revision, and persistence. The value society assigns to creativity is often proportional to the effort behind it. The “struggle” of the artist is a culturally embedded narrative that enhances appreciation. When a painting or a poem is created by an AI with no sense of self, intention, or emotional experience, critics argue it may lack the very essence that gives art its value.

2. The Historical Relationship Between Art and Technology

To evaluate whether AI threatens creativity, it’s useful to look at historical precedents. Art and technology have always been intertwined. The invention of the camera in the 19th century, for instance, led to anxieties about the death of painting. Yet photography emerged not only as an artistic medium in its own right but also transformed how painters approached realism and abstraction.

Similarly, the advent of digital tools such as Photoshop, Procreate, and computer-generated imagery (CGI) raised questions about authenticity and skill. Critics initially dismissed digital art as “less real,” but over time, these technologies became accepted as valid creative tools. The tools changed, but the human artist’s vision remained central.

AI can be seen as an evolution of these tools — more complex, autonomous, and algorithmically intelligent. However, unlike brushes or software, AI can now generate outputs with little to no human input after the initial programming or prompting phase. This autonomy is what differentiates AI art from other technology-assisted art forms and intensifies the debate.

3. How AI Generates Art

Modern AI art is primarily powered by machine learning techniques, especially deep learning and generative models like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and transformer-based models. These systems are trained on massive datasets of existing artworks, texts, or music compositions and then generate new outputs based on probabilistic predictions and learned patterns.

For instance, OpenAI’s DALL·E and Midjourney generate visual art from textual prompts, while GPT-based models can write poems or screenplays. Music AI like AIVA and Amper Music compose melodies mimicking classical or contemporary styles. These systems do not “understand” art in the human sense; they replicate styles, motifs, and structures based on data patterns.

The key point here is that AI does not possess consciousness, emotion, or intention. Its outputs are statistically generated, not emotionally experienced. Yet, in many cases, the results are aesthetically compelling and indistinguishable from human-made art. This raises the question: if a machine can produce emotionally evocative art without feeling, is emotion or intention even necessary for creative value?

4. The Arguments Suggesting AI Diminishes Human Creativity

Several critiques assert that AI art undermines the value of human creativity in various ways:

a. Devaluation of Effort and Skill:

AI-generated art, particularly when created with minimal input (e.g., typing a prompt into a generator), raises concerns about the devaluation of the artistic process. Centuries of artistic skill, labor, and training seem sidelined when AI can mimic a Rembrandt or compose a symphony. If anyone can generate stunning visuals with a few clicks, the exclusivity and respect traditionally granted to artists may erode.

b. Dilution of Originality:

AI systems are trained on pre-existing data, which means their outputs are essentially remixed versions of prior works. Critics argue that such outputs are inherently derivative. When art is no longer the result of an individual’s unique experience or worldview, but rather an algorithm’s interpolation of others’ creativity, the notion of originality suffers.

c. Threat to Creative Professions:

Artists, illustrators, writers, and musicians increasingly face economic pressure from AI systems capable of producing low-cost alternatives. For freelance creators or small studios, the commodification of art via AI platforms can lead to job loss, de-skilling, and reduced artistic agency. The monetization of AI-generated content also raises ethical issues about ownership and consent—many AI models are trained on datasets without artists’ permission.

d. Erosion of Cultural and Emotional Depth:

While AI art can simulate emotion, it does not experience it. Art rooted in cultural memory, trauma, or lived struggle may not be faithfully captured by a machine. Critics argue that such works, though visually impressive, lack depth, meaning, and the ineffable “soul” of human-made art.

5. The Case for AI as a Tool That Enhances Human Creativity

On the other hand, proponents argue that AI does not diminish creativity but rather augments it:

a. Expansion of Creative Possibilities:

AI enables artists to experiment with forms, styles, and genres they might not have otherwise explored. By offloading repetitive tasks or providing unexpected inspirations, AI can help artists iterate faster and refine their vision. For example, an illustrator may use AI-generated sketches as drafts, then personalize and complete them by hand.

b. Democratization of Art:

AI tools make creativity accessible to those without formal training or resources. Someone with no art background can now generate digital paintings or compose music. This democratization challenges elitist notions of creativity and opens the door for broader participation in artistic expression.

c. Collaboration, Not Replacement:

Many contemporary artists use AI as a co-creator. The process involves curating datasets, fine-tuning models, and selecting or manipulating outputs. This hybrid approach retains human agency while expanding artistic boundaries. For example, artist Refik Anadol uses AI to create immersive data sculptures that visualize collective memory.

d. Reframing Creativity Itself:

AI challenges the romanticized, individualistic view of creativity. If creativity can emerge from networks, feedback loops, and collective learning (as in the case of AI), perhaps our definitions of creativity need updating. Some argue that intelligence—artificial or not—capable of producing meaningful art should be recognized as creative, albeit in a non-human way.

6. Reactions from the Artistic and Philosophical Community

Artists are divided in their response to AI. Some embrace it as a medium—like paint or photography—while others reject it as a commodification of art. Philosophers like Margaret Boden and Daniel Dennett suggest that creativity can be mechanistic to an extent, but others insist on the irreducibility of human consciousness and intention.

The Turing Test has often been used to evaluate AI intelligence. In art, a similar test might ask whether a viewer can distinguish between AI- and human-made art. But this test doesn’t fully capture what matters in art. The knowledge that a work was made by a person—who suffered, dreamed, or rebelled—often deepens its impact. The “backstory” becomes part of the art.

Some ethicists worry about “ethical laundering,” where the use of AI distances creators and consumers from accountability. For example, if an AI generates offensive imagery or mimics a marginalized culture, who is responsible? Such issues suggest that even if AI art is creative, it exists within a complex ethical ecosystem that human art has long inhabited.

7. The Future of Creativity in the Age of AI

Looking forward, several trends are likely to shape the intersection of AI and creativity:

a. Hybrid Artistic Practices:

Art will increasingly emerge from human-AI collaborations, with artists directing, editing, and imbuing AI outputs with personal meaning. These hybrid forms could create entirely new genres, much like photography or digital animation once did.

b. Legal and Ethical Frameworks:

The rise of AI art demands legal clarity on copyright, attribution, and ownership. Questions like “Who owns an artwork created by an AI trained on public datasets?” or “Should AI be credited as a co-author?” remain unresolved. These issues will affect how creativity is valued and protected.

c. Cultural Shifts in Perception:

Public attitudes toward AI-generated art may evolve. Just as digital art gained legitimacy over time, AI art might eventually be seen as valid in its own right. However, it will likely coexist rather than compete with human-made art, occupying different symbolic and emotional registers.

d. Emotional AI and the Illusion of Sentience:

Future AI may simulate emotion more convincingly—perhaps even adapting in real time to audience responses. While still not “feeling” in the human sense, such systems could create deeper illusions of authenticity, further blurring lines between real and artificial creativity.

Conclusion

The use of AI in art does not categorically diminish human creativity. Rather, it compels us to reconsider what creativity means, who gets to be called an artist, and how we define the value of artistic work. While there are legitimate concerns about devaluation, economic displacement, and loss of emotional depth, AI can also serve as a powerful catalyst for new forms of human expression.

Creativity has never been static. From cave paintings to VR installations, it evolves with our tools, our societies, and our needs. AI is the latest chapter in that story — not an end to creativity, but a mirror reflecting its complexity, potential, and resilience.