The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) as a tool for artistic creation has sparked intense debate across disciplines—art, philosophy, computer science, and beyond. From AI-generated paintings auctioned for hundreds of thousands of dollars to music, poetry, and literature created with the help of machine learning algorithms, the line between human creativity and artificial production is increasingly blurred. This raises a fundamental philosophical and aesthetic question: Is AI-generated art truly “art,” or is it merely the output of an algorithm? This essay argues that while AI-generated work is rooted in computational processes, it can still qualify as art—if one adopts a broad, evolving understanding of artistic authorship, creativity, and interpretation. The discussion will examine the nature of art, creativity, and authorship; the mechanics and philosophy behind AI art; counterarguments from critics; and possible resolutions to this contentious debate.

Defining Art: Humanistic vs Expansive Views

To evaluate whether AI-generated work is “art,” we must first define what art is. Traditionally, art has been considered a uniquely human endeavor—an expression of thought, emotion, culture, and intent. Philosophers such as Tolstoy viewed art as a medium for the transmission of feeling from artist to audience, while others like Clive Bell emphasized “significant form” and aesthetic experience.

However, contemporary definitions of art have evolved to be more inclusive and postmodern. Institutional theory, for instance, claims that art is anything that is presented as art within the context of the art world. Arthur Danto and George Dickie argued that art does not rely on inherent properties but rather on context and interpretation. This opens the door to considering even algorithmic output as art if it is exhibited, interpreted, and experienced as such.

Thus, we can distinguish two broad schools of thought:

- Essentialist (Humanist) View: Art must involve intentional human creativity and emotional expression.

- Expansive (Contextualist) View: Art is defined by how it is received, interpreted, or institutionalized, regardless of origin.

If we adopt the former, AI-generated work may fall short. But under the latter, it can plausibly qualify as art.

What Is AI-Generated Art?

AI-generated art refers to artistic content created with the help of artificial intelligence technologies—most commonly, deep learning models such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), or transformers like GPT and DALL·E. These systems are trained on vast datasets of human-made content, learning statistical correlations and patterns that they use to generate novel outputs.

Importantly, AI art often involves human intervention at various stages:

- Data curation: Selecting the training data.

- Algorithm design: Configuring the model and parameters.

- Prompting: Inputting specific text or variables to guide output.

- Selection and editing: Choosing and refining results.

Thus, most AI art is not created in a vacuum. It’s a co-creative process, with human agency present alongside machine learning mechanisms.

Creativity: Can Machines Be Creative?

Creativity has traditionally been considered a hallmark of human intelligence, involving originality, intentionality, and the capacity to generate meaning. However, AI challenges this notion.

Margaret Boden, a leading theorist on creativity, distinguishes three types:

- Combinatorial creativity: Recombining existing ideas (e.g., remixing).

- Exploratory creativity: Navigating within a conceptual space (e.g., painting in the style of Impressionism).

- Transformational creativity: Altering the conceptual space itself (e.g., inventing Cubism).

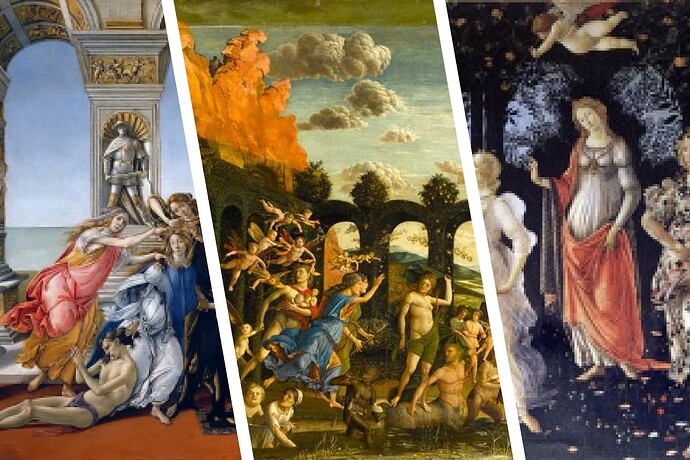

AI clearly exhibits combinatorial and exploratory creativity. For instance, GANs can combine features of thousands of paintings to generate new ones. Transformers like GPT can synthesize literary styles. But transformational creativity—changing the rules—is harder for AI, as it relies on programmed or learned patterns rather than autonomous innovation.

Yet even human creativity is rarely ex nihilo. Artists, writers, and musicians borrow, remix, and The concept of the “lone genius”” is largely a myth. In this light, AI’s mimetic process mirrors human creativity more than it may first appear.

Authorship and Intent: Who (or What) is the Artist?

A major critique of AI-generated art is that it lacks intent—an artwork, critics argue, must be the product of conscious intention. A painting by Picasso reflects his personal vision; a poem by Sylvia Plath reveals her emotional landscape.

But intent is not always central to artistic value. The Dadaist movement, for instance, emphasized randomness and absurdity. John Cage’s composition 4’33” involves no deliberate sound but is still considered music. Moreover, the interpretation of intent often lies with the viewer, not the artist.

AI complicates authorship further. Who is the “author” of an AI-generated painting?

- The algorithm? It lacks consciousness and legal agency.

- The developer? They created the model but didn’t design each output.

- The user? They prompted and selected the result.

The answer may be all or none. Like photography in the 19th century, which shifted authorship from painting to camera usage, AI introduces a new kind of authorship—dispersed, layered, and hybrid.

Case Studies: When AI Art Made Headlines

Several landmark cases illustrate the cultural impact and controversy of AI-generated art.

- Portrait of Edmond de Belamy (2018)

Created by the French art collective Obvious using GANs, this portrait was auctioned at Christie’s for $432,500. It sparked global debate on AI’s role in the art world. Critics asked: Can an algorithm create a masterpiece? Was the value due to novelty or artistry? - Refik Anadol’s Data Sculptures

Anadol uses AI and big data to generate immersive installations that visualize the hidden patterns of memory, dreams, and landscapes. His work is celebrated in major galleries, raising questions about the boundaries between art, architecture, and algorithm. - BotPoet and AI Poetry Competitions

AI-written poems have won literary competitions, even fooling judges into thinking they were human-made. This challenges assumptions about language, emotion, and authorship.

These examples suggest that AI art is not only technically impressive but also socially and economically impactful—hallmarks of artistic legitimacy.

Philosophical Objections and Responses

Despite its growing recognition, AI art faces strong philosophical opposition.

Objection 1: AI Lacks Consciousness and Emotion

Argument: Art is an expression of subjective experience. Since AI lacks self-awareness, it cannot “feel” or “intend.”

Response: Art can evoke emotion without originating from emotion. A photograph or abstract painting may move us deeply even if it was generated through chance or mechanical means. Moreover, the emotional impact is often generated by the audience, not the creator.

Objection 2: It’s Just Imitation

Argument: AI merely mimics human patterns. It does not innovate or struggle, and thus cannot create true art.

Response: Many human artists are also inspired by predecessors. Influence and imitation are central to the evolution of art. AI’s capacity to recombine styles is itself a kind of innovation—especially when guided by human prompts or novel datasets.

Objection 3: It Devalues Human Creativity

Argument: If machines can create “art,” it may undermine the value of human effort and skill.

Response: Rather than replacing artists, AI can augment human creativity. Many artists use AI as a tool or collaborator—similar to how Photoshop, synthesizers, or cameras enhanced creative possibilities.

Legal and Ethical Considerations

AI-generated art also raises practical questions around copyright, ownership, and ethics.

- Copyright Law: Most jurisdictions do not grant copyright to non-human entities. Thus, AI-generated works may be in a legal gray zone. Courts and legislatures are currently grappling with how to handle such cases.

- Plagiarism: Since AI learns from existing works, does it risk plagiarizing? If a model is trained on copyrighted art, and generates a derivative work, is it theft?

- Bias and Representation: Datasets used for training may reflect societal biases, which are then reproduced in AI art. Who is responsible for this?

Ethical use of AI in art demands transparency, accountability, and respectful use of source material—issues not unlike those faced by traditional artists and scholars.

Audience Reception and Meaning-Making

An essential aspect of art is its reception. If an audience finds meaning, beauty, or emotional resonance in an AI-generated work, does it matter how it was created?

Reception theory in art suggests that meaning is not fixed by the creator, but constructed by the audience. Roland Barthes declared the “death of the author,” emphasizing that interpretation lies in the eye of the beholder.

From this perspective, AI art is “real” art if it functions like art in the social and aesthetic lives of people.

Historical Parallels: Technology and Art

Art has always evolved with technology—and each time, purists resist the change.

- Photography (1800s): Dismissed by painters as mechanical. Now a respected art form.

- Film (early 1900s): Once considered lowbrow entertainment. Now studied as high art.

- Digital Art (1990s–2000s): Skeptics claimed it lacked “real” technique. Now mainstream.

AI art fits into this trajectory. It may currently seem alien or “less authentic,” but history suggests that new tools eventually become accepted media of artistic expression.

AI as a Tool vs AI as an Artist

One useful distinction is between using AI as a tool and viewing AI as an artist.

- As a tool, AI is like a paintbrush, synthesizer, or camera. Artists control it to express human intent.

- As an artist, AI would require autonomy, creativity, and intent.

Currently, AI is arguably still a tool—albeit a highly advanced one. But as models become more autonomous and generative, the line may blur.

Some propose the term “synthetic artist” to describe AI systems that can produce unique, impactful works without direct human instruction.

Implications for the Future of Art

The rise of AI art is not just a technical or philosophical issue—it has profound implications for:

- Art education: Should students learn to prompt AI, curate datasets, or critique machine-made works?

- Art markets: Will collectors value AI art? Or will it flood the market, reducing exclusivity?

- Art institutions: Should museums and galleries exhibit AI work? How will it be curated and preserved?

- Art therapy and accessibility: Can AI democratize creativity, allowing people without formal training to create expressive work?

In all these areas, AI challenges us to rethink what it means to be creative, to be human, and to make art.

Conclusion

So, is AI-generated art truly “art,” or merely algorithmic output? The answer depends on how we define art, creativity, and authorship. If we cling to essentialist definitions rooted in consciousness and human intent, AI art may seem inauthentic. But if we embrace broader, more contextual definitions—grounded in reception, function, and experience—then AI-generated works can indeed qualify as art.

AI art is not merely cold computation. It is a mirror reflecting human culture, aesthetics, and imagination—processed through an algorithmic lens. Like any new artistic medium, it invites critique, experimentation, and wonder.

In the end, perhaps the more important question is not whether AI-generated works are art, but what kind of art they are—and what they reveal about the evolving relationship between humanity, technology, and creative expression.